Città Universitaria – the pride of Fascists: between academic monumentalism and rationalism

On a relatively small, rectangular land plot with a surface area of two hundred twenty thousand square meters, a university complex was created which would bring together tens of buildings, that would, in turn, fit ten thousand students and professors, but also research institutes as well as additional structures, such as bars, a preschool, a post office a bank, and even the offices of the university militia.

The ambitious undertaking was led by one of the foremost architects of Fascist Italy, Marcello Piacentini, who once again displayed tremendous organizational talent. The designs of individual faculties were entrusted to architects from various parts of Italy. Their selection varied greatly – this group included (reportedly at the behest of Mussolini), both Modernists (academic monumentalists), as well as proponents of Rationalism. Stylistic unity was not required – on the contrary: the city was to represent stylistic pluralism but also prove the modernity of Italian architecture, which used not only marble and columns but also reinforced steel constructions and glass. Piacentini was tasked with creating a compact and homogenous complex and finding a compromise between the architects of the older generation – renowned professors of architecture (Rapisardi, Foschini, Aschieri) and young aspiring architects who were just starting out in the profession (Pagano, Michelucci, Capponi).

The urban concept was based on the plan of a forum with the main building of the Rectory (Palazzo del Rettorato), around which the head offices of each individual faculty were concentrated.

It was possible to access the complex from various sides, however, the representative entrance was situated at Piazzale delle Scienze (present-day Piazzale Aldo Moro), where monumental covered with travertine propylaea with a double row of supports were placed. They were accessed by an equally monumental, sixty-meter wide avenue, with the Rectory located at its axis. However, prior to reaching it, it is worth taking a look at two broad buildings flanking the propylaea, which house the Institute of Hygiene and Bacteriology as well as the Clinic of Orthopedics and Traumatology. Their bodies with raw elevations filled with rows or regularly spaced windows were made out of brick, while the travertine is used only to underline certain elements, such as the portals. Both buildings were designed by Arnaldo Foschini, a valued architect of the Fascist era, a professor of architecture, and the author of numerous buildings, including the interesting Church of Santi Pietro e Paolo, situated in another flagship architectural complex of the Fascists – the Roman EUR district.

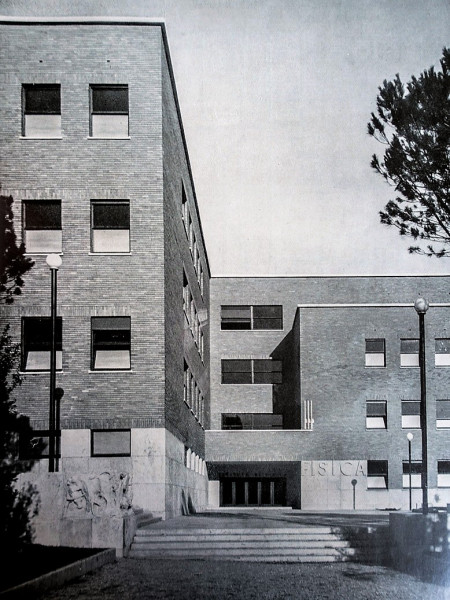

Subsequent structures located on either side of the avenue are the Institute of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics. The first one was designed by Professor Pietro Aschieri, a creator who searched for a compromise between Monumentalism and Rationalism in architecture, whose most significant work was the Museum of Roman Civilization, in the aforementioned EUR district. However, here Aschieri used reinforced concrete constructions and proposed simple, brick elevations. The Institute of Physics situated directly opposite is the work of Giuseppe Pagano. This architect of Croatian descent was a declared representative of the rationalist approach. As was the case with all architects who cooperated with the regime, he was initially a member of the National Fascist Party and enthusiastically took part in the “Fascist revolution”, but in 1943 he joined the underground movement against Mussolini. Captured and tortured, he died in the Mauthausen concentration camp, immediately prior to the end of the war.

In this way we have come to the very heart of the university complex – the covered in travertine Rectory designed by Piacentini himself. The main entrance of the building leads through a protruding giant portico resting on four columns. This is in truth the only distinguishable element of this very monotonous building, whose style can be described as simplified Neoclassicism. Entering the building via high, pyramid-like stairs (as if in a base of an Egyptian temple), going through the monstrous portico, followed by an enormous gate, into the vestibule adorned with green and grey marble and shining bronze balustrades, one had to feel in awe of the enormity of this building, and thus implicitly in awe of the greatness of Fascist Italy. And still today we feel intimidated by the enormous proportions of this building. And all this without even entering the great hall, which is the main room of the Rectory building. The hall which is rather modest in its decorations could once fit three hundred students. It was decorated only in the proscenium part, with a monumental painting entitled Italy between Art and Science, completed by the favored of the regime, albeit very skilled painter of those times Mario Sironi.

The broad façade of the Rectory is flanked by two wings (the Institute of Law and Political Sciences and the Institute of Literature and Philosophy), which constitute an ideally integrated whole. They were designed by an architect who had cooperated with Piacentini for a long time – Gaetano Rapisardi. Their raw elevations are adorned with reliefs depicting the Dioscuri.

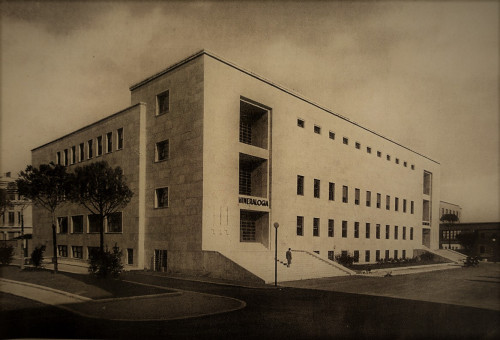

In front of the Rectory, there is a statue of Minerva (the goddess of wisdom) – the work of Arturo Martini -, which is visible all the way from the propylaea of the main entrance as it reflects in the waters of the pool immediately in front of it. It is around this statue that all the buildings, broad avenues, and squares of the complex are centered. It is also the center of an enormous (68 meters wide and 240 meters long) Piazzale della Minerva. At one of the shortest sides of the square stands the Institute of Mathematics, at the other the Institute of Mineralogy, Geology, and Paleontology. The first building is particularly interesting, designed by an architect of the younger generation (Giovanni Pino), whose real career would not begin until after the war. However, it was here that he first showed his above-average talent. As he said in one interview “you require pure architecture from architects, pure as crystal”, and that is what his body of the building, covered in travertine is like. It appears as a gigantic cube. The only decoration of its elevation is a glazed cutout in the central part of the façade, which lets light into the interior. As it would turn out, this is only the beginning of the planned complex, because this cube in the rear part transfers into a semi-circular atrium which in turn is finished off with a semi-circular hall. This is, therefore, a complex of excellently planned raw forms which hide behind an avant-garde façade of the initial building. The Institute of Mineralogy, Geology, and Paleontology is, on the other hand, the work of Giovanni Michelucci – a representative of classical Modernism. He created a building that fit in well with the works of his fellow architects – a simple, functional, distinguishable by two tracts of high stairs of the main façade.

Moving onto the back of the Rectory, we will see the broad silhouette of the Institute of Botany and Pharmaceutical Chemistry, which is one of the most interesting buildings of the university complex. This is the work of one of the youngest architects, Giuseppe Capponi, which is an excellent example of rationalist architecture but also evidence of the inspiration of young Italian designers with the then European architecture, in this case, German. The glass towers, situated in the central part of the building boast a novel construction: their central part is closed off with a wall, but their edges are surrounded by seemingly glazed surfaces. Capponi who was also known for his scenic design died a year after completing the design, not living long enough to see the completion of a complex of the Cinecittà buildings, in whose creation he also participated.

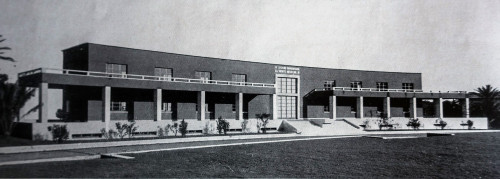

Besides the buildings of the individual institutes of large size and complex plans, there were also numerous smaller ones, which were characterized by simple, yet interesting designing solutions. One of these is the University Militia Station (Casermetta della Milizia) designed by two architects – Gaetano Minnucci and Eugenio Montuori. The prism of the building is only separated by high windows, with an exposed, glazed part of the main entrance, adorned only with the surrounding terrace. The building housed the headquarters of the militia and an ambulatory, but also a gym for the Fascist youth. In addition, Minnucci, also designed the Fascist Resting Home (Dopolavoro e Circolo del Littorio). On the ground floor, there was a reading room, a bar, a pool hall, a fencing and gymnastics hall, changing rooms, as well as a cinema-theatre hall for two hundred fifty people; on the first floor, there were rooms designated exclusively for professors and their assistants – among them once again a pool hall, a bar, a reading room, and even a ballroom. The facility also included a tennis court, a volleyball court, and a pétanque terrain. As we can see the regime wanted to provide the academic staff with ideal conditions for work and relaxation – of course, the chosen few. It is worth mentioning that they had to swear an oath of fidelity to the Duce, and those who did not lost their professorship. At the Sapienza University only four professors refused to swear this oath (Ernesto Buonaiuti, Giorgio Levi della Vide, Gaetano De Sanctis, and Vito Volterra).

The Città Universitaria complex was completed after three years of construction in 1935. Its grand opening occurred in the presence of King Victor Emanuel III. In total it is made up of nearly forty facilities. The stylistic diversity but also a new way of constructing buildings with the use of reinforced concrete and prefabricated elements, as well as a lack of decorative details, not only decreased construction costs but also decisively sped up the work rate, arousing admiration throughout Europe. Mussolini's regime proved not only its efficiency and dynamism but also the high quality of its architecture, which was to a large extent the work of young architects, who could boast novel designs, yet immersed in completely Italian culture. Mussolini became not only an excellent and robust leader but also a visionary in the field of architecture. Fascists had reasons to be proud and pleased – the complex quickly became known as the best structure constructed during the Fascist era. And truly looking at it from today's perspective, some of the buildings, for instance, those completed by Capponi (the Institute of Botany) and Ponti (the Institute of Mathematics), are novel designs by all accounts, one could even say avant-garde. That is not to say that the structures built by the architects of the older generation – raw, restrained, and linear with repeating modules are any worse. In all of these arrangements, with long perspectives and broad squares, there is something heroically monumental, but also metaphysical. Stylistic pluralism – reportedly forced onto Piacentini by the Duce – turned out to be quite creative in the long run. The structures which were built here later fit in perfectly with the urban tissue of the thirties. For instance, the Church of La Divina Sapienza (Piazzale Aldo Moro) which was designed after the war and finished in 1952 – also by Piacentini, who from a favorite of the Fascist regime, quickly turned into an important architect of the Italian Republic. The structure made out of brick fits perfectly with the street which leads to it. The body of the church, in the form of a roller, is filled with small round windows. The dome, on the other hand, was placed directly on the wall (without a tambourine), thanks to which the church maintains balanced proportions, appropriate for a university chapel.

Purity, order, and cleanliness – that is what we can see on the illustrations (which I have also used here) of the Fascist-controlled (as was all the press at the time) magazine „Architettura” published for the opening of the complex. In the introduction to this particular issue, Marcello Piacentini praised Mussolini and his government. As he claimed, it was thanks to the specific political and ideological atmosphere created by the regime, that it was possible to create such a well-thought-out complex. However, Piacentini did not write that, any student or professor or anybody else who would find himself in the city of his creation should feel like a cog in the giant machine of the state, a state which cares for him, but also thinks for him. It is here that the characters of the new generation of Italy were to be shaped – subordinate, submissive, and devoted to the regime. Their behavior was carefully watched by the campus militia, ready to intervene at any time.

Today, the chaotically parked cars, scooters, and bikes of the students and professors, as well as the broad-reaching trees covering the viewing axes destroy this harmony. Students smoking cigarettes and eating pizza on the pompous stairs of the Rectory know very little about the surrounding architecture and most assuredly they do not feel like an element of a planned, large-scale concept of order and rigor. The complex teeming with life does not fulfill the task which it was supposed to, at least in the ideological dimension, but it is a testament of the times when it was possible.